Why we don't see more women quizzers

Issue #95: The many gender-based barriers in the world of quizzing

Hello ji,

Over the course of 12 years of formal schooling, I changed 10 schools. The upside of always being the ‘new girl’ is that I learned the art of making friends superfast. A clear downside is that very few of my friendships from school have made it into adulthood.

One of the handful of friends that have made the cut is a boy (well, now man) who was my teammate in a school quiz. Specifically, it was the ‘Maruti Quiz Contest’- a popular inter-school quiz in the 90s - and the two of us made it to the finals.

All I remember from that final is that it was nighttime and we were both giddy to be able to do cool quiz stuff outside the school boundary and school hours. Our parents cheered us from the audience as we won… probably nothing, but had a bucketful of fun at it.

Cut to my first year of college.

A college festival was on and I wanted to participate in the quiz.

Minor hiccup: Our college culture drew a line of control between the boys and girls, forbidding pretty much any cross-border interaction, at least in the first year. And no one on the girls’ side of that line seemed as interested in the event as I was.

I somehow managed to form a team and we made it to the finals - apparently the first “girls’ team” to do so in the student body’s memory. I remember the applause we got when this fact was highlighted by the quizmaster. And I had bucketloads of fun cracking the questions, some of which I remember to this day.

But there were some other bucketfuls thrown over this memory which made it quite different from the pure joy I remembered from that Maruti quiz as a kid.

To begin with, I remember having to beg two other girls to participate in the quiz just so I had a team. Even after the team was registered, I remember the very real fear - all the way to the end - that they would back out at any time. And I remember spending most of my energy not on the quiz, but on ensuring their mental comfort at all times.

A bucketful of pain.

I remember that the quiz finals were - once again - held at night. I remember the hostel warden refusing to allow us permission to step out of the confines of the girls’ hostel beyond hostel timings. I remember running from pillar to post, getting seniors and professors to sign a host of letters and undertakings about our safety, just to get the hostel warden’s grudging (and heavily conditional) permission.

A bucketful of shame.

I remember walking into the quiz and seeing just a sea of men around. As a female student in an engineering college with a 1:10 gender ratio, I was no stranger to being the only woman in a room. But there was something about being there after dark, with many male students clearly under the influence of alcohol, and several clearly there just to enjoy the rare sighting of female specimens wandering around campus at night.

A bucketful of discomfort.

And I remember sensing each applause we got for a right answer, tinged with just a hint of surprise. A subtle cocked eyebrow here, a loud “WTF BRO!” there. Each one, a reminder that our presence here was an anomaly.

A bucketful of exclusion.

Gatekeeping of ‘worthy’ subject matters

I have wanted to write about Womaning in the quizzing world for a long time. Recently, I came across a viral Twitter thread that nudged me into finally doing it.

Avid quizzer, Ria Chopra, shared the story of a quiz answer from her school days that she remembers to this day.

She went on to share how - even though she knew she had the right answer - she ultimately asked her male teammate to say it because she did not want to be typecast as the “supermodel quizzer”.

I reached out to Ria and asked her if she thought that her gender played a role in the feeling that her (male) teammate could give her answer, but she couldn’t.

Here is what she said:

“Yes, the concern of feeling judged by other quizzers for knowing the name of a supermodel is definitely a very gendered fear. I have been a quizzer for many years now, and have seen many women being labelled as ‘fashion quizzers’, or ‘movie quizzers’, etc. because they answered one or two pop culture questions.

This phenomenon – of putting quizzers into boxes based on a few questions they answer, especially if they are pop culture questions – is something that happens almost exclusively to women in quizzing circles.

Even at that young age, I knew instinctively that if I answered that question, I would be labeled the "supermodel quizzer" and that this tag would follow me at every future quiz.

Actually, I had answered plenty of other questions in the quiz that related to a variety of subjects - dates, monuments, history, geography, all of it. But I knew none of that would be remembered if I gave this particular answer. So I asked my teammate who, predictably, was immune to such labels because he was a boy.”

Ria went on to say that boxing women into a restrictive label in quizzing is just a reflection of such labels attached to women in all fields of knowledge.

“We give a man the liberty to be many things at the same time. But we want to reduce a woman to the lowest common denominator of all the things she might be.

Look at Kim Kardashian, for example. She is a lawyer, she is a model, she has starred in music videos. She owns own her clothing and makeup lines. She has written a book and done many other things. But she will forever be described as a "reality TV star" or a "socialite" or some other label that has a derogatory connotation to it.

If a man had started from reality TV but gone on to do all these things later in life, we would all know him today as an entrepreneur, or a bestselling author. The most respectable of things he has done would be highlighted. This labeling is gendered and we see it happen in quizzing all the time.”

Even the hierarchy that defines what the “lowest common denominator” stands for comes with a bias.

“Things that women know better, or are usually more interested in - say, entertainment, lifestyle, fashion - are devalued because women know them.

Crypto-currency has had zero impact on most of our lives, but the clothes we wear affect us deeply on a daily basis.

Yet, a quiz question about cryptocurrency would be considered a more important ‘general knowledge’ question than one about fashion. Why?

It makes no logical sense.

There is only one explanation: By the simple virtue of women being more active and interested in fashion, it is devalued as a field of knowledge. In fact, even knowing a little bit about it becomes a matter of shame.”

Ria says that these stereotypes are traps for women quizzers.

“A label is hard on any quizzer. Especially when it is force-fitted on you with you having no choice in the matter. It can tarnish your entire quizzing experience. If a woman is labeled a ‘supermodel quizzer’ (like I could have been that day), she is trapped - because if you answer supermodel questions now, you are feeding into stereotypes. And if you don't, you are a failure for not even living up to your supposed area of expertise.”

Akshaya is a regular in the Chennai and Bangalore quizzing circuits. She shared the perfect example of this happening to her.

“Quiz questions (usually set by men quizmasters) often revolve around topics that men consider worthy, like sports, hard rock music, etc. Even within pop culture, quiz questions are almost always about male celebrities.

And when it is a question about women, they expect the woman on the team to have all the answers. For example, questions about the first female anything - the first female artist to win an award, or first female doctor, etc. - create a Catch-22 for me.

If I know the answer, it is tricky to give it because I've heard folks say ‘She knew it because that is a girly answer’.

And if I don’t know, I am chided, ‘Oh this was a girly topic, yeh bhi nahi pata tha kya? (Didn’t you know even this?)’

I don’t know why men assume that women walk around with the entire life history of Annie Besant imprinted in their brains just because she was a woman, and know nothing about David Bowie because he was a man.”

Ananya Giri Upadhya is another active quizzer and one who was never particularly interested in fashion as an area of knowledge. But that did not stop her fellow quizzers from making assumptions based on her gender.

“On two separate occasions, assumptions have been made about my prowess as a fashion quizzer just because I am a woman.

Once, an older male quizzer suggested to me that I represent my team in the solo fashion round.

Another time, I was the quizmaster for a group with a large number of men, and a man suggested fashion as a possible topic for me to set my quiz on.”

Ananya is pursuing her BA LLB from National Law University, Delhi, where she recently did a sociology project on ‘Quizzing in India’.

In her report, she writes:

“Quizzes, with their focus on popular culture, tend to draw heavily from books, movies, television or online shows, and music. But only those that the same circle of quizmasters, who double up as quizzers, consider ‘worthy’ of consumption. (This is) accompanied by the presumption that everyone (would) have consumed these, and can answer questions about them.

(But) the media consumed by this small circle is very different from real popular culture… (They consume) Hollywood productions, a few critically-acclaimed or cult Indian films, Western music, and literature that is either classic or recent critical successes. Those who do not follow the same media – out of lack of either access or interest – end up deprived of the deep, specific knowledge required to answer these questions that masquerade as testing one’s ‘general’ knowledge.”

She writes about the “gatekeeping of worthy topics” by senior quizzers:

“There is a clear trend of gatekeeping of ‘worthy’ topics from a gendered lens. Topics such as fashion, romantic comedies, Bollywood, TikTok, boy bands are disapproved of… Fans of Korean Pop (“K-Pop”) and users of TikTok are routinely mocked and referred to as ‘cringe-worthy’.

Ananya recalls a quiz where women quizmasters conducted a round with questions around TikToks with a popular music connection.

“Despite it being sufficiently ‘general’ to allow male quizzers to answer most of the questions, it was met with loud disapproval. One of them was annoyed at having lost points for not knowing (something as ‘unworthy’ as) the Jonas Brothers, a chart-topping boy band.

She shared this brilliant video, that hilariously mocks how some men passionately gatekeep the definition of nerds - where knowing everything about Lord of the Rings is considered impressive, but knowing everything about Barbie is dismissed as frivolous.

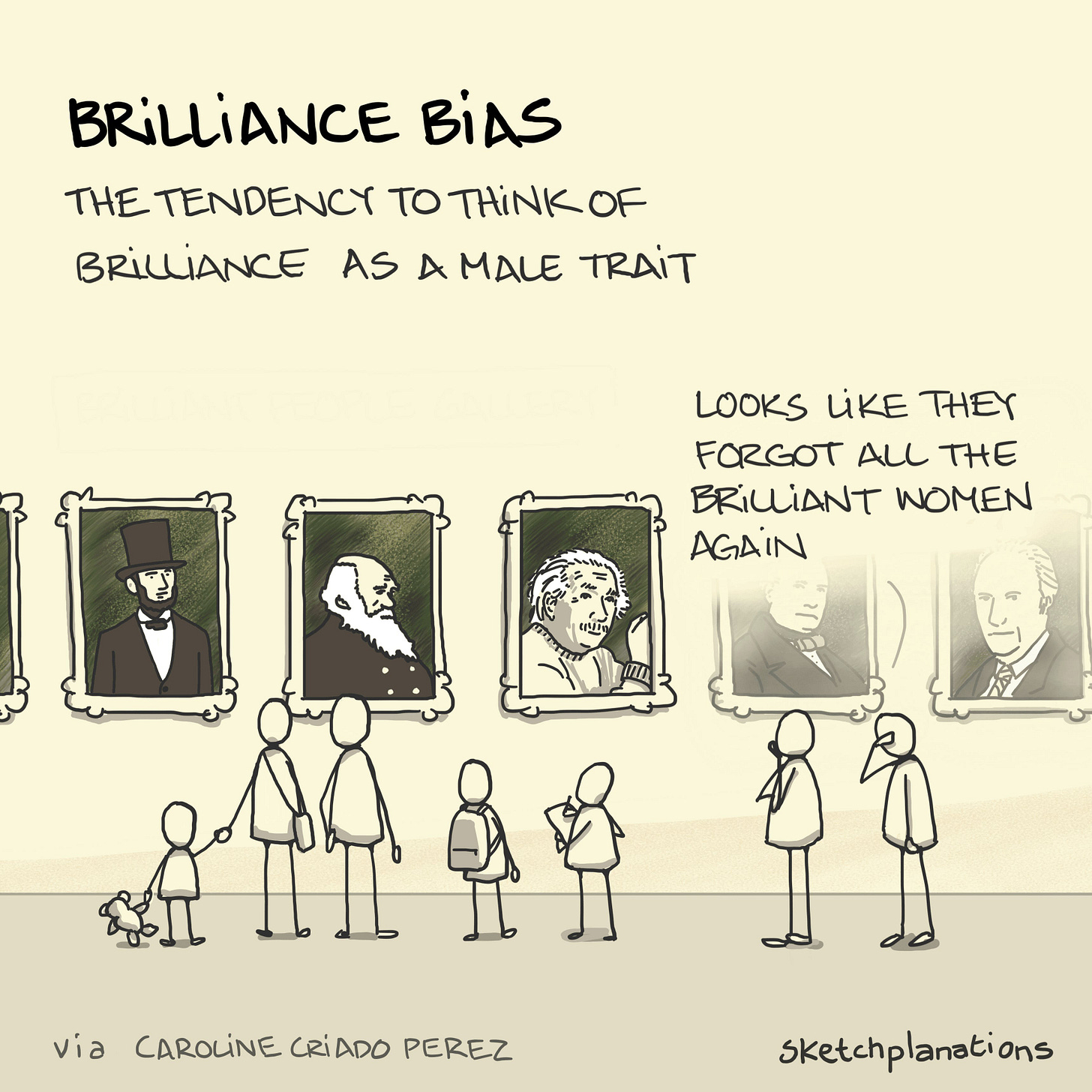

The brilliance bias

Brilliance is seen as a male trait. Therefore, any woman’s brilliance is seen as an anomaly.

Amita spoke to me about the unjustified surprise expressed when women quizzers answer questions not related to the supposed ‘girly’ topics.

“I often get a look of surprise from quizmasters and other participants when I answer a question that is supposedly not in the ‘female’ territory. This happens every time I answer a question related to, say, sports or automobiles. For the longest time I used to take that look of surprise as a compliment.

Now, I know better. So I directly ask them, ‘Why are you surprised?’”

Another side-effect of being the only woman in a room is that, apparently, it makes you the representative of our entire gender.

Ria says:

“If a guy doesn't know a sports question, he is a bad sports quizzer. But if a woman doesn't know a sports question, women are bad sports quizzers.”

There are four billion women in the world. Imagine if you were suddenly made the representative of four billion people without your consent or qualification. It is a heavy cross to bear.

“This stops a lot of women quizzers from experimenting in new fields of interest. It stops women from making guesses and taking chances at getting things wrong every once in a while - all foundational aspects of becoming a quizzer.

This is because we fear that if we get something wrong, our entire gender will be denigrated for it. This is a huge discouragement.”

Team dynamics

The brilliance bias also has an impact on dynamics inside and between teams comprising women.

Mallika shared an example from her quizzing experience:

“When I am the only girl in a team, I often find myself getting overridden over answers I want to give. I recently had a serious talk with my teammates about this. I gave them several examples where I had the right answer but they overruled me.

They accepted that it is not this hard for male teammates to convince other teammates to submit their answers in the face of disagreement, and said they would be more conscious in the future.”

Ananya writes about this:

“Sweeping generalizations are made that women quizzers are not as good as their male counterparts simply because they do not come to enough quizzes to prove their worth. Men might consciously avoid teaming up with women (or approach men first). This also means a lack of ‘mentors’ – experienced male quizzers offer young men guidance with a frequency they do not show when it comes to young women. Experienced women quizzers are simply too far and few to fill the void.”

Ria spoke about another dynamic that makes even the act of forming a quiz team as a woman a challenge:

“As a woman, your team-making is always questioned. I have always made teams for completely common quizzing reasons - I want to team up with people who are great quizzers, or who fill my knowledge gaps. When others invite me to join their team, it is usually for the same reason.

But when a man and a woman team up, rumours inevitably start flying. People say things like, ‘Oh, they teamed up so they must be dating’ or ‘She is sleeping with him so that she can team up with him’ or ‘He is interested in her (romantically), that is why he is teaming up with her’.

A woman being a good quizzer is somehow never a thought that occurs to people. This constant questioning of your talent or merit as a quizzer can really get you down.”

The time and place

The fact that both my lasting memories from quizzing are of late-night quizzes is not an aberration. Ananya writes:

“Quizzers often note that the numbers of female participants at quizzes are highest in school but dwindle successively at college and beyond.

Perhaps the most obvious structural barrier in quizzing is safety-related concerns. While young women face travel restrictions or curfews from family or educational institutions, older women also avoid commuting in the evenings or nights. On the other hand, men are usually allowed to travel across the country for quizzes and to stay late at local quizzes to socialize.”

Bad timing might seem like a minor inconvenience to men, but quizzes being held at or overflowing into the night is one of the biggest barriers in the way of greater women’s participation in quizzing.

I spoke with Smriti, a quizzer who had not even considered this as a barrier until our conversation.

“Oh, I just remembered now that you asked me about this. The quiz meets in my college would be held in the boys hostel, where girls were simply not allowed after hours. I just accepted it without question at the time. I am finding it very amusing now that I didn't even notice this because I am so used to discrimination and bias.”

Komal says that a recent chat with a male quizzer showed her that little has changed since her college days:

“In my undergrad college, all the quiz tryouts would happen late in the night, after the girls’ curfew time. So obviously no girls could participate. Even during the college fest, quizzes were scheduled during late evenings. So, not only could girls not participate, we couldn't even watch the event to build a passing interest in quizzing.

Recently, I was talking about the lack of women in quizzing with a male quizmaster, and he said it was unfortunate that the women had a curfew. It didn't even occur to him that he can choose to schedule the events at a more inclusive time.”

Akshaya says that almost all quizzes she has attended - including informal ones - start and end late.

“This is a big hurdle because pub and informal quizzes are how one gets their foot in the quizzing door. But if I don't have a male companion ready to drop me home, I simply cannot participate in these quizzes.

The KQA (Karnataka Quiz Association) is much more sensible on that front. They do weekend quizzes starting at 10am. Even their evening quizzes usually end early, or simply happen online. Such scheduling practices need to be encouraged if we want more women in quizzing.”

Ria echoes that having trustworthy male friends willing to drop you home is a privilege and that it should not be a pre-requisite for a woman to participate in a quiz.

“Most quizzes start 2 hours after their scheduled time, and end 5 hours after the scheduled time, making it physically impossible for women to get back home safely.

I have often had to miss quizzes because I knew they would run late. Many women quizzers live in hostels, PGs, etc. where they have a curfew. 99% women will simply not go for a late evening quiz, while men will not even realize that this is an issue.

Once you have friends in the quizzing circuit, you have the privilege of asking someone to drop you home. But imagine you are a college student participating in your first quiz, or are new to a city, and you do not know anyone yet. You don't know who can become a supportive friend and who can become a creepy stalker. How will you ask someone to drop you home?”

There is an easy fix for this, of course, and Ria has been practicing it too.

“We need to schedule quizzes earlier. Start at 10am instead of 3pm, and try to adhere to the scheduled timings. When I am a quizmaster, I make it a point to start my quizzes within 15mins of the scheduled start time. But I don’t see a lot of quizzers doing that. People want to wait for the audience to grow, or to wait for some specific people to join. This is a clear discouragement for potential women participants in such quizzes.”

Boys’ Club, harassment, and exclusion

Over years and decades of these barriers working their magic, most quizzing circuits have become trapped in a vicious cycle. The presence of only a few women forges a strong boys club, which, in turn, discourages women to join.

This boys club dynamic manifests as inside jokes and late-night after-parties at best, and casual sexism and even sexual harassment at worst.

Smriti talks about the exclusionary feeling that the boys’ clubs can give fresh quizzers, especially women.

“When you first enter such a quiz club, you might not even recognize the language they are speaking. They often use abbreviations, slangs, and codenames that no outsider recognizes. They have inside jokes that they will crack to loud laughter and much back-slapping, as you silently watch, feeling like an unwelcome outsider invading a private club.

As a man, you can still hope to slowly become a part of the gang. You will get invited to (and be able to attend) late-night after-parties. You will probably become drinking buddies with the older quizzers. You might even crack a sexist joke or objectify a woman quizzer behind her back, and that might earn you favours with some men and help you become an insider on the fast track. I have personally heard of many such jokes cracked by men at these parties with no women around.

But as a woman, you will literally never become an insider. You might not be invited to, able to, or even willing to join these inside clubs. And that will come with the side-effect of you never finding a mentor, because the men will never see you as one of their own. Overtime this will hamper your growth as a quizzer.

It is not surprising that only a handful of women are able to break this barrier and survive as serious quizzers.”

Komal recollects a recent experience where she felt like an outsider at a quiz:

“I went for a quiz club meet-up in a new city. I was the only woman there in a group of all men who were very tight and had a lot of inside jokes. I struggled to even have anyone make eye contact with me. During a quiz they conducted at the meetup, I was randomly assigned to a team.

The men on my team clearly didn't like having me on the team. They did not ask me if I knew the answers to any of the questions. When I did give one answer, they reprimanded me for not discussing it with them before answering. I decided never to go for these meetups after that.”

Ananya talks about how this exclusion can make quizzing spaces unsafe for women:

“Being subjected to curiosity or objectification may affect the confidence of a female participant in a crowd full of men. Being more objectified – or feeling more objectified (due to increased sexual awareness) – after puberty might be related to the decline in the number of female quizzers during and after high school.

Prominent quizzers called out for sexual harassment have subsequently been either socially boycotted or have faced no repercussions. In the latter event, the victim would reduce her quizzing to avoid contact with the harasser.”

Ria added to what she told me about ulterior motives being ascribed to women’s team-making.

“There actually are times when men will ask you to team up with them with actual ulterior motives. As all women know, men will try to use any and every platform to hit on women - whether it is the workplace, a classroom, or even your LinkedIn DMs. A quiz is no different. Many men see it as a potential space to find dates. But most women don't go to quizzes for dating. I go to a quiz to test my knowledge, to learn something new, to have fun. It is a problem that women cannot be seen as just quizzers. Your quizzing talent takes a backseat, especially if you are a single woman.”

This seemingly harmless ‘hitting on women’ by men can quickly take an ugly turn.

A few years back, a spate of sexual harassment complaints against male quizzers in several Indian quiz clubs led the Bombay Quiz Club to publish a Code of Conduct. Maitreyi, who was a part of the team that put it together, says:

“Around the time of the MeToo movement, incidents came to light where male quizzers had allegedly harassed women they met at quizzes. Even what men consider ‘harmless flirting’ can make quizzing deeply uncomfortable for the women involved.

We decided then to come up with a Code of Conduct because we know of some habitually offensive characters at quizzes who make the environment uncomfortable for women with their distasteful comments.

We were the first club in India to put out such a Code and since then, a few other clubs have followed suit. Just the presence of such a code seems to have made a difference and we have had no incidents reported since we started sharing it at quizzes.”

So what can be done to make quizzing more inclusive?

There is a reason my memories from my own quizzing journey pretty much end with my first year in college. I was one of the thousands of Indian women who - in the face of the above barriers - had to quit quizzing despite having both interest and capability to pursue it further.

How do we curtail this brain drain?

Most of the answers are already hidden in the stories above.

Quiz clubs need to take conscious steps to make quizzing a more inclusive and welcoming experience for everyone.

The timing and venue of quizzes should be chosen in a way that does not render half the population unable to participate.

The old notions of ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ knowledge must be shed. If quizzing is for nerds, we need to accept that nerds can come from any area of interest. Fashion nerds are as valid as Lord of the Rings nerds.

A formalized policy against exclusionary behavior will go a long way for some ‘habitually offensive characters’ to take a hint that the times are a-changing.

Finally, as Ria put it so well during our conversation:

“We need more women quizmasters. The men leading most quiz clubs in India today could help by requesting more women to join them in organizing quizzes. Gender-based blind spots are only blind spots for men. Most women see them clearly. Get a woman's perspective. She might be able to help you organize a much more inclusive quiz - with an inclusive venue, timing, questions, etc. Most importantly, her sheer presence is sure to encourage more women to participate in or attend the quiz.”

Quizzing is something that literally anyone and everyone can pursue. And it has the potential to bring bucketfuls of joy to people from all backgrounds, ages, backgrounds, and genders.

The final question - for all the points - is, ‘Do we want it to?’

Mahima

❤️ Love Womaning? Show it by becoming a paid subscriber or getting yourself some choice Womaning merch.

🔥 If you are an aspiring writer - or even someone who just wants to make their emails shine - check out my storytelling course, which includes writing workshops and one-on-one mentoring to help you write better, write consistently, and launch your own newsletter.

Thanks so very much for this, Mahima. As another commenter says, you did in fact bring out the detailed nuances of discrimination in quizzing.

You so rightly pointed out, the quizmasters were *always* men, and the pop culture references (as an example) were all about hard rock or metal music, which I had simply never been exposed to (I still don't know how they were even exposed to it since in the 90s we were all fairly equally gareeb with no internet access, and the only songs I could listen to were the ones on DD2's "top ten music countdown" and the Carnatic music cassettes my father loved to collect.). And not knowing that was somehow uncool or made me a bad quizzer or lacking in general knowledge.

As you also rightly pointed out, even just being at a quiz was so intensely uncomfortable, a handful of girls in a sea of boys. Our college (one of the NITs, a supposed source of national pride) had this street from the entrance where all the boys (seniors as well as the juniors they were grooming) sat and "hooted" at the girls passing by. SO INFURIATING. And the same kind of "hooting" happened at events where the gender ratio was abysmal (which means *every* event in our engineering college). Why would any of us even *want* to be there? But on the other hand, HOW DARE THESE GOONS stop us from attending an event which we could have otherwise enjoyed?

Besides quizzing, Mahima, in engineering colleges, we also often had "techfests" for which the lab where we could build our robots and whatnot were located outside the hostels and so, by design, were inaccessible to girls at night (due to the in-time), the only time we could reasonably work on that stuff, after classes and dinner. That's why none of us girls could even participate in these things, thus missing out on a ton of learning.

I also loved that you brought up the notion of brilliance: In our engineering college, we had girls ranking first in almost all the departments (I was one of them a couple of times too). Still, some of my good male friends would say something to the effect of "Verma isn't a topper because wo padhta nahin hai; but wo hai genius; you and those other girls come first only because tum log poora din padhte ho". It was SO INFURIATING. Nothing we did could be enough. I will be graduating with a fucking PhD in computer science from a top-5 institute in the US, and I will start my postdoctoral research at MIT in July. Still, I know that to these guys, it'll always be because "main poora din bas padhai karti hun". FWIW, this myth of the male genius is all-pervasive in US academia as well, so we must not be too proud to claim it as our desi culture.

I can never forgive the boys (and admins) of my college for making *our* college so unwelcome to us. I hope some day they truly learn the hard way how terrible they've been as persons. And no, being 19 does *not* mean it's ok to do that stuff; I was 19 too then, and I did *NOT* make *you* uncomfortable.

(Sorry, I got so intensely angry responding to this post; your post was PHENOMENAL, Mahima. Please keep writing!)

Really true. I used to hate that General quizzes would be so full of sports and video games questions. I'm glad this is being talked about. Thank you Mahima.